Here’s another lengthy set of remarks culled from lectures I gave for the British Horror Film course from a few years ago. This time the subject isn’t Tod Slaughter but Scream and Scream Again (1970), a peculiar film that brings together a disparate set of genres, tones, and narratives, few of which cohere with each other, though the result is nonetheless a pretty compelling and (at times) remarkably boring horror movie, which is no mean feat.

As those of you who stuck around last Tuesday night already well know, the film we’re going to be talking about this week, Scream and Scream Again, poses a number of challenges to interpretation that speak to some of the things I allusively tried to prepare the grounds for during my position statement last week right before the Thanksgiving holidays. For starters, there’s the fact that the film is a generic mess, a shambling assemblage of discordant moves and archetypes, a distractingly clumsy mash-up of conspiracy thriller paranoia, by-the-book police procedural forms, Swinging London iconography (“I love you, man!”), parodically outsized (and presumably Cold War-instigated) totalitarian fantasy projections supposedly giving us a peek behind the Iron Curtain (though that reading gets quickly enough troubled and undone once you start to apply a little pressure to it), and (finally) horror-ish signifiers (a vampire serial killer, Vincent Price, Peter Cushing, and Christopher Lee, oh my!). The obvious (but no less essential) thing to note about Scream and Scream Again’s unseemly clutter and general untidiness is the degree to which the film’s unruliness seems to be related to the threat the movie does not so much contain as it open-endedly represents and (dare I say it) embodies. That is to say, Scream and Scream Again is as much a composite as are the living dead superhumans being designed by Dr. Browning with his applicator and his fabricator. The film, in short, is a beefed-up, amped-up, sped-up assortment of distinctive parts that all seem to be governed by a design that is not itself reducible to the functions and expectations normally attached to those parts, at least not when they show up in a British horror film from the late 1960s and early 1970s.

In this respect, therefore, it’s perhaps helpful to keep in mind that Dr. Browning’s revelations at the end of the film don’t really tell us anything that would help us to make sense of what it is we just saw. For instance, to take the most obvious (but no less important) example: nothing Browning says satisfactorily explains why Keith is a vampiric serial killer instead of just another normal run-of-the-mill serial killer, like the real-life (if not quite contemporaneous) Yorkshire Ripper who terrorized England and killed thirteen women between 1975 and 1980. In fact, Keith’s activities and the police effort to catch him are evidently such a consequential sub-plot or composite element in the film that Keith’s protracted chase and death scene gets fifteen minutes of screen-time in a ninety-five minute film, meaning that Keith’s failed escape and his successful suicide take up almost twenty percent of the film itself. Yet despite this conspicuous focus on Keith’s clumsy escape attempts and his acid-bath death, all Browning has to say about him is that Keith was his first composite with “autonomously functioning brain patterns,” but that does little to help you understand or account for in a tidy sort of way why Keith’s “autonomously functioning brain patterns” lead him to rape, brutalize, and drain the blood of young women out on the town for a shag. In short, much like Keith, the film itself is much in need of our interpretive efforts because the explanations and motivations with which Dr. Browning very elaborately regales Dr. Sorel at the end of the film very noticeably leave a lot of stuff explained, not only with respect to the narrative itself but also to the world that that film attempts to build up in its ample (and disorienting) use of match-cuts as it moves from story-to-story, from genre-to-genre, and from zone-to-zone.

Allied to the composite-style of which Scream and Scream Again is cussedly comprised, a remarkable lack of piety toward this thing called “The British Horror Film” also seems to get strikingly demonstrated again and again throughout the movie. Another way of saying this would be to note that what the film presents us with is decidedly not the “English gothic tradition” so stridently singled out and generously described by David Pirie in his book-length study of British Horror. To be sure, we do indeed find a vampire amidst all the stitched-together pop culture detritus of the film, but this isn’t a Hammer (or even a Universal) vampire. Far from being the stuff of Byronic anti-hero legend that Pirie reliably sees instantiated with varying degrees of approximating success in Hammer’s long run of Dracula flicks, Keith, the vampire serial killer in Scream and Scream Again, does not seem to embody familiar British gothic archetypes so much as he does a set of evacuated preconceptions that neither he nor the film makes much effort to thereafter fill in or flesh out for us. That is to say, sure, Keith’s a vampire, but the film doesn’t really give us the sorts of vampire business (like close-ups of the bite marks) to which we’ve grown accustomed by the Hammer house style, nor do we ever get to see Keith baring his canines as he moves in for a gulp from the jugular. Similarly, the rationale for Keith’s bloodlust is so non-existent that evidently it doesn’t even rate a quasi-logical cover story. Nothing Dr. Browning says suggests that Keith’s vampirism is a necessary supplement to his living dead superhuman-ness. We have no reason to suspect that Keith needs blood to stay alive, meaning that we’re thrown back on trying to interpret this wildly inconsistent movie in terms of the elusive motivations of its wildly inconsistent characters, who seem to have overdeveloped fantasy lives, of which the film does not make always let us partake or catch more than a glimpse. Unlike a lot of the other films we’ve been watching this quarter, it would perhaps be fair to say that Scream and Scream Again doesn’t much care about putting together a coherent cover story for us, nor does it seem to think that this is a problem. Instead, its incoherent cover story simply is the case, like it or lump it.

While I do not want us to ever lose sight of this incoherence or of this doubled inconsistency at the level of the film itself and of the motivations of the film’s characters themselves, I do nevertheless want to make a start here today of addressing these confusing and maybe even nonsensical features of the text by way of a long detour into figures and national film traditions that have not yet come into our view this quarter in the British horror films we’ve watched up to this point. The reasons for this detour are easily enough justified because you all ought to know up-front that I understand Scream and Scream Again’s symbolic investments and pieties as being not at all reducible to the British film-making milieu, industrial arrangements, and reservoir of citational material with which you’ve all grown quite adept at recognizing, analyzing, and making use of in novel ways these past eight or so weeks. Instead, the argument I’m making today would have you all believe that Scream and Scream Again evocatively scrambles the tools you all have been working with because its main intertextual points of reference exist across a range of times and national spaces that seem to have little to do with Pirie’s much-vaunted “English gothic tradition.” At the risk of speaking schematically, I think we can reduce these points of references to at least two orders, which I will list for you now and then spend a good chunk of today’s lecture detailing at greater length.

Our first point of reference (and the one I am going to spend almost all of today’s lecture talking about) comes from German popular cinema from the 1920s to the 1960s (in other words, from Weimar Germany through Nazi Germany and out the other side in a Cold War-set Western German milieu), and this point of reference goes by the name of Dr. Mabuse, the great criminal mastermind, anti-hero, and supposedly allegorical embodiment of all that went wrong with German history following World War I. Our second point of reference is more concisely expressed and comes from a near future that was just becoming discernible at the time Scream and Scream Again was in production, and this point of reference goes by the name of the conspiracy film, perhaps the American film genre par excellence in the 1970s.

Let me go back to my first point because it needs a bit more unpacking. If I had time today, I would build up another German point of reference, one that comes from West German popular cinema, but from a later period that roughly overlaps with the years of Hammer’s rise and fall (roughly speaking, from the late 1950s to the early 1970s), and this point of reference goes by the name of Kriminalfilms (Krimis for short), which more generally means crime films but in this period tended to refer principally to German-language adaptations of the pulpy crime novels of an early twentieth-century British writer (Edgar Wallace) by a Danish and German film studio called Rialto Pictures. Because I don’t have the time to develop linkages between Scream and Scream Again and these comic-book-like and downright goofy Krimis (parenthetically, I would note for you all that the best imaginative approximation of these films for those of you who haven’t seen them is to think about a Sean Connery James Bond film shot like an hour-and-a-half-long Scooby-Doo cartoon episode, complete with endings in which the killer gets unmasked by the snoopy Scotland Yard investigators, and you’ll be damn awful close to any given Krimi), I’ll very briefly describe them to you and why they might be worth your time.

These films are fascinating intertexts for a course like this because Rialto’s Edgar Wallace Krimis are pretty much West Germany’s answer to Hammer Horror. That is to say, if there’s a popular cultural property of the 1950s, 1960s, and early 1970s instantly recognizable as “West German,” it’s these Krimis, and they’re pretty neat intertexts with Hammer horror when you start to think about them together. For starters, if most of the canonical Hammer films are set in a Hammerland that’s supposed to be the Europe or Eastern Europe of the nineteenth century or earlier, then these Edgar Wallace Krimis are also all set in a place we can take to calling Krimiland, which is supposed to be a mid-twentieth-century West German’s pop imaginary representation of mid-twentieth-century London, where evil secret organizations (often led by men and women who wear strange masks and colorful disguises) face off against the good secret organization called Scotland Yard. A lot of jokes at the expense of the Brit’s stiff upper lip are made, huge quantities of poisoned tea get consumed, remnants of a decaying aristocratic class get unmasked for the decadent wastrels that they are, and the bourgeois-fied members of this remaindered landed gentry end up winning the vast inheritance and marrying the dashing Scotland Yard investigator. I would also note for you all that though these films always show Scotland Yard coming out on top, along the way the Yard’s detectives let a lot of people die, either through incompetence or boneheaded negligence.

There’s a lot more to be said here, but the thing to hold onto here is the sort of supranational work that is being done in Hammer films and in these Krimis in order to make more imaginable or thinkable something like an integrated and integral Europe. Think of both as pop culture anticipations of the European Union from the Cold War period. Although I’m not going to be able to talk about these West German Edgar Wallace adaptations in any sort of detail, I would like to give you a taste so you have a sense of what it is we’re dealing with here. Here’s a clip from The Monk with the Whip (1967), in which a boarding school headmistress, done up in a lurid blood-red monk outfit, terrorizes the teaching staff and student body of her all-girl school somewhere in the countryside just outside of London. Here are the opening four minutes of the film:

I don’t have the time to go into any sort of detailed analysis here, but let it suffice for me to point out to you that if we start in a British horror film—that is to say, if we start in a lurid Eastmancolorized mad scientist film—then by the end of the credit sequence we’re pretty securely situated in Krimiland, replete with a Scooby-Doo villain whose dramatic entrance is scored with an organ music cue that segues quite jarringly into the poppier jangle of late 1960s Euro-jazz that’s such an integral part of this film and of Scream and Scream Again. Compare this opening credit sequence, with the red monk figure approaching the camera as the credit rolls, with the opening of Scream and Scream Again, where our unfortunately disoriented man approaches the camera as the credits splay out over him and as the Euro-jazz pap plays:

If I had more time today, I would stress the importance of Scream and Scream Again’s credit sequences as the place where the film starts cueing viewers for a perceptual experience in which Krimis—and not Hammer or its British knock-offs—are the film-watching and -making models to be followed. As I don’t have time to do this, however, I’ll let that claim loom over us for a bit as I move on.

In a nutshell, what we have here is a complex weave of styles, figures, tropes, narratives, filmmaking traditions, national cultural properties, and temporalities informing the intertextual network that Scream and Scream Again establishes, which is a roundabout way of saying that all the problems presented by Dr. Browning’s composites remain with us still. Saying that these film traditions or figures or genres or modes are the principal ones being evoked by Scream and Scream Again does not make the untidy hash of things described by the ill-fitting assemblages in that film’s narrative, style, or characters go away. What starts as a mess, in other words, is going to stay a mess, but at least now we have a bigger mess to work with and select from in interpreting the film. I ought also to fess up at this point and tell you all that the mess is going to stay a mess throughout this lecture, which is to say that I am not leading you all down a path at the end of which stands a perfectly coherent and singularly reconstituted Scream and Scream Again. Instead, at 3:45 we’re still going to be stuck with a countless number of composites (composite narratives, composite styles, composite intertexts, composite histories, composite national cultures, etc.), and if there’s any goal I have in view for my commentary today, then that goal is that we all will have a better sense of how to coherently talk about the incoherence of Scream and Scream Again’s compositeness. Another way of putting this would be to say that while I am trying to do justice to the film’s compositeness, I am not at all going to be faithful to its incoherence.

The other preliminary thing that I ought to signpost for you all a bit more forthrightly has to do with this issue of the Britishness of the British horror film. For starters, for those of you thinking about writing about Scream and Scream Again for your final paper, I would strongly encourage you to re-read the material written by Andrew Higson in the course reader on the idea of national cinema. I really don’t have the time to belabor this point (though it is a point well worth belaboring), but I do want to gesture toward the Higson chapters in order to pose the following question, and I want all of you to mull over this question as you continue thinking about Scream and Scream Again this week: if we start from Higson’s cultural valence of the concept of national cinema—that is to say, if we assume that the concept of national cinema in the case of Scream and Scream Again is preeminently a cultural notion as opposed to an economic one—then what sort of mass identity is being affirmed in a “British” film where the primary cultural traditions being negotiated are non-indigenous so long as we approach the “British Horror Film” in terms of its “Britishness”? In a nutshell, what’s so British about Scream and Scream Again? Alternatively, just how German is it?

The tentative answer I am offering today would have you all believe that Scream and Scream Again ruptures the sorts of national frameworks that this course has provisionally put around the films it has shown you up until now because the indigenous and shared cultural traditions that this film imagines (and would have you imagine along with it) derive from a continent-wide reservoir of cultural properties that traverse a supranational unit, like that of the European Coal and Steel Community or the European Economic Community or (finally) the European Union. In short, I want you all to start thinking about the necessity of approaching this film in terms of a broader European film culture and horror film tradition because my readings today and my hunches today all express in one way or another a principled dissatisfaction with the capacity of certain jealously guarded and nationally demarcated film concepts and tools to adequately open up Scream and Scream Again to adequate interpretation.

This has been a long, roundabout way of saying that there is more than one way to study British horror movies, and the purpose of my comments in this our final week is simply to shake things up a bit and get you all to start thinking about British horror films not so much in terms of “indigenous” film traditions but rather in terms of pan-European cultural interchanges, exchanges, and product differentiation. For instance, a useful sort of question to ask in this vein would be the following: what do the Hammer Dracula movies look like after we take into account Italian vampire films from the 1950s, Spanish vampire films from the late 1960s, and French vampire films from the 1970s? Alternatively (and more interestingly perhaps), I can’t help but notice that it would be very instructive to juxtapose Hammer Dracula and Frankenstein movies with the principal contemporary horror icons from other European countries, like the figure of the witch in Italy or the wolfman in Spain or lesbian vampires in France or Dr. Mabuse in West Germany. In short, what happens when we replace Great Britain with the figmentary (but no less powerful) idea of a unified Europe as our referent for these “British” horror films? With those questions asked and those observations expressed, we can begin to talk about the Scream and Scream Again by way of that shadowy criminal mastermind, expert hypnotist, and counterfeit artist, Dr. Mabuse, arguably the most popular anti-hero of German popular cinema and the subject of twelve official Mabuse films made over the course of seventy years.

For most contemporary non-German film-viewers, however, the name “Dr. Mabuse” conjures up visions of an auteur because the film-maker most commonly associated with Dr. Mabuse is Fritz Lang, who directed and co-wrote the first three Dr. Mabuse flicks: Dr. Mabuse: The Gambler (1922), The Testament of Dr. Mabuse (1933), and The 1,000 Eyes of Dr. Mabuse (1960). Following The 1,000 Eyes of Dr. Mabuse, Artur Brauner, the producer who owned the rights to Dr. Mabuse in the post-war period, began cranking out campy remakes and sequels to the original Mabuse trilogy, and these serially-produced sequels and remakes borrowed a good deal both from 1960s spy films and from the Krimis being churned out by Rialto films in West Germany at the same time as well, but I’ll bracket that connection for the now and focus instead on the three Lang Mabuse films.

All you need to know about the first three Mabuse movies is that they all involve an “evil” mastermind who threatens the existing social order with his well-coordinated criminal organization, whose unparalleled efficacy at carrying out its anti-social misdeeds often seems to make existing society its uncanny double. That is to say, these films reliably tend to suggest that the institutions and fidelities of a Mabuse-led or a Mabuse-inspired criminal underworld would make the world run more smoothly because they actually accomplish what they set out to do, unlike existing police forces, market economies, and national governments, which all stumble, falter, and outright fail with far too much regularity to be of much service or help to the billions of people they manage, govern, and police worldwide. Alternatively, Mabuse’s criminal underworld, particularly in the first Mabuse film, tends to get read allegorically quite literally as an “image of the times” such that Mabuse’s criminal activities are meant to be interpreted as thinly-veiled representations of supposedly more socially acceptable crimes, like speculative finance in the time of currency inflation in early 1920s Weimar Germany or increasingly invasive surveillance technologies in the Cold War-era. In short, the boilerplate or commonplace critical assumption regarding the Lang Mabuse trilogy is that they present us with three “images of the times” that are all certainly different but that all nevertheless share a conspiratorial world-outlook that becomes increasingly harder and harder to localize in the figure of Dr. Mabuse himself as the twentieth century unfolds. Mabuse, after all, goes mad at the end of Dr. Mabuse: The Gambler, and then dies halfway through The Testament of Dr. Mabuse. The criminal organization that carries out its terroristic campaign in early 1930s Germany does so using the notes written by Dr. Mabuse in his insane asylum, and in The 1,000 Eyes of Dr. Mabuse, “Mabuse” is simply a name adopted by a new criminal mastermind who follows Mabuse’s Weimar- and Nazi-era example. In other words, Mabuse is not really Mabuse by the early 1960s. What we have here, then, is the evacuation of Mabuse as a person and its re-inscription (by way of Mabuse’s notes, his last will and testament) into a subject-position that anyone else (or, alternatively, that any number of people) can fill should they aspire to become criminal masterminds who are also images or symptoms or allegories of their times. In short, what we find in the Lang Mabuse films is an overarching narrative in which the name, “Dr. Mabuse,” becomes more and more abstract and less and less personalized such that anyone could be a Dr. Mabuse in potential.

I would further add that we know that Scream and Scream Again ought to be preliminarily approached as an unofficial Mabuse film because the West German distributors somewhat cynically re-titled the movie The Living Corpses of Dr. Mabuse and re-dubbed the movie so that Vincent Price’s Dr. Browning underwent a name change to Dr. Mabuse. In other words, film distributors in Germany saw a way of cashing in on the renewal of the 1960s Dr. Mabuse craze by introducing minimal differences into a British and American-financed film whose paranoid and totalizing outlook onto a Cold War world system seemed to already make that film legible as a Mabuse movie to West German nationals in the first place. In other words, Scream and Scream Again’s updated conspiracy narrative with self-destructive and singular anti-heroes behind it all seemed to jive with the sorts of cultural preconceptions and expectations raised by the Dr. Mabuse figure himself in the mid-to-late 1960s. Compare, in this respect, the rationale behind the Mabuse-conspiracy given by Dr. Baum in The Testament of Dr. Mabuse with the account given of the Mabuse-like conspiracy by Dr. Browning in Scream and Scream Again. In this first clip from The Testament of Dr. Mabuse, we have Dr. Baum describing the genius of his patient, Dr. Mabuse, to police inspector Lohmann as they stand over the body of Dr. Mabuse himself. Take a look:

Now compare this to a similar scene at the end of Scream and Scream Again:

There’s obviously a lot to be said about these two scenes and their relationship to each other, but for our purposes today I want to focus on two things. For starters, the scene from Scream and Scream Again seems to pointedly revalue Dr. Baum’s description of Dr. Mabuse, such that the sorts of things Dr. Baum celebrates Dr. Browning disparages, and the sorts of things Dr. Baum disparages Dr. Browning celebrates. For instance, the godlessness of the Weimer Republic in the early 1930s seems to be an occasion for welcoming the terror and horror that Dr. Mabuse’s singularly “phenomenal, superhuman mind” instigates in his last will and testament’s call for an anarcho-fascist campaign of terrorism targeting all levels of society: finance, energy production, heavy industries, transportation, etc. are all ripe for destruction so that humankind can be purified of and by its own propensity for violence, self-destruction, and mass extermination. There’s a sort of homeopathic quality to Mabuse’s testament in this film, such that the acts of terrorism that his written words impeccably put into action after his death are simply amplifications of the daily acts of terrorism (like mass unemployment) that already confront Germans in the interwar period but that are more or less countenanced because they are accepted as being part and parcel of modernity. In other words, terror and horror already exist as a baseline of social experience in Weimar Germany, but their presence has been obscured precisely because they are such a commonplace feature of modern human life, and what Mabuse calls for (according to Dr. Baum) is a series of criminal undertakings meant to apocalyptically unveil these baseline social experiences for the acts of quotidian terrorism they in fact are once and for all. All of Dr. Baum’s talk of a regrettable lack of justice or compassion is just a feint or a ruse, therefore, to cover up the real problem with Weimar Germany in the early 1930s, which is that it wasn’t frightening enough because its citizens were just too damned jaded to be scared by much anymore. Obviously, this is the point where the Mabuse-as-Hitler or Mabuse-as-proto-fascist readings have a field-day, and it certainly has a scary sort of force as a culture critique that does seem plausible on its face: by the early 1930s, this Mabuse-as-Hitler argument would have you believe, Germans were so jaded that even the rise of German National Socialism wasn’t enough to scare them back into their senses. I don’t know that that approach gets you much farther than these sorts of pithily aphoristic glosses, but you can’t deny them a certain force all the same.

Curiously, Dr. Browning’s big speech in Scream and Scream Again invokes such From Caligari to Hitler readings by its use of something like reverse discourse. That is to say, Dr. Browning tries to reclaim Dr. Baum’s speech by repurposing or revaluing the negative connotations attached to its terminology, both within Lang’s film itself and in the history of German National Socialism. Instead of presenting us with the “superhuman” in terms of wholesale destruction, terror, and horror, Dr. Browning makes the important qualification that while what he is describing to Dr. Sorel certainly looks an awful lot like a super-race, it really ought not to be understood as an evil super-race. This sort of revaluation can be seen throughout Dr. Browning’s speech (think for example of his celebration of the condition of our godlessness, which inverts Dr. Baum’s assertions in Lang’s film).

However, if Dr. Browning really is our Dr. Mabuse, then he’s a less obviously malevolent Mabuse-figure, for rather than taking humankind’s proclivity toward mass extinction as a mandate for speedily exterminating all human life, Dr. Browning interprets it instead as a call for greater and greater control of men and women by a super-race of scientists who (in twenty years time we’re told) will be ready “to act for the good of humanity,” though (as with much else in this movie) of what such acts will likely consist is left pointedly undisclosed. What gets stressed in its place (and what Dr. Sorel’s questions reliably point out) is the technocratically totalitarian nature of Dr. Browning’s post-sixties Mabuse-like plan, which is to say that it presupposes a caste of superhuman rulers and a caste of human subjects ruled by those superhuman rulers. Our latter-day version of Dr. Mabuse may be kinder, gentler, and look a whole hell of a lot more like Vincent Price than Fritz Lang’s Mabuse did, but the keynote here still remains one of the conspiratorial subjugation of the masses, by means of terror and horror in the earlier film and by means of a presumably genetically-modified biological dispensation in this one that is meant to look more like benevolent and competent caretaking than it does terroristic purification.

The other thing that ought to interest us about the connections between this scene and the one from The Testament of Dr. Mabuse has to do with Dr. Sorel’s initial reaction to Dr. Browning’s revelations: “So, you’ve created life. It’s the old mad scientist’s dream. Let’s play God.” What leaps out at me here is the explicit way in which this part of the exchange between Browning and Sorel negotiates the shifting cultural fields of reference at play throughout the scene. In other words, what interests me here is the way in which Dr. Sorel starts to interpret Dr. Browning’s speech in terms of a British horror film only to have Dr. Browning himself laugh off that interpretation in favor of the more plausible one: Browning sees Sorel’s Frankenstein and raises him . . . a Mabuse. Unlike Mabuse, Frankenstein, it will be remembered, was never much of a team player, and in the Hammer films he tends to sit uneasily either within, at the head of, or at the edges of institutional frameworks. Mabuse, on the other hand, as you all are discovering, is all about institutions, he’s all about massive vertically integrated criminal organizations at the top of which sits him and him alone. In short, Dr. Sorel’s failure to interpret the sort of horror movie that Dr. Browning and he are in corresponds with his failure to grasp more fully the newly totalizing dimension of the problem he now faces. If only things were as simple as they often are in a Frankenstein film, if only the problem were that of one head too many or one head too few, then maybe Dr. Sorel could throw together some sort of hasty solution that would satisfactorily patch things up until the sequel. After all, Frankenstein himself really is the individual most responsible for the problem with the surplus heads and bodies, it is he who is singularly responsible for all this cinematic over-generativity or surplus-productivity, so all you need to do is lop off his head, or maybe just wait until he and the film he is in gets bored with the mere fact of production, right? As I said earlier, however, Dr. Mabuse is a lot more slippery a figure, not least of all because he progressively evaporates as Lang’s three films proceed, and his subject-position increasingly becomes occupiable by any and all comers clever enough and bureaucratically-minded enough to put into play globe-encompassing conspiracies involving petty theft, blackmail, terrorism, speculative finance, explosive feats of engineering, and closed circuit television surveillance systems. Moreover, Scream and Scream Again presents us the frightening prospect in which humans as such do next to nothing. You’ll remember that the climactic fight involves three superhuman Mabuses facing off against each other while our two humans make their escape.

Parenthetically, I want to interrupt myself here in order to point out that the interesting thing about this confusing-Frankenstein-with-Mabuse business is that it also gets at an interesting feature of the formal composition of Scream and Scream Again, which has to do with its witty use of match cuts. You all will remember from Evan’s lecture on the Hammer Frankenstein films that match cuts in those films provide a model for assembly. Conversely, the Fritz Lang Mabuse movies tend to operate by the disorienting use of cross-cutting, whereby you are plopped down in one narrative only to be jerked abruptly from it and thrown into another narrative already in progress, meaning you’re constantly hard-at-work bringing yourself up to speed, trying to figure who’s who and what this story has to do with the other story you were just in. The neat thing about Scream and Scream Again is that it does both of these things: half the fun is trying to figure out where you are in a given plot and what that has to do with the other plots already presented, much like in a Mabuse film; the rest of the fun comes from the smart and silly editing tying these various plots together from scene-to-scene. Consider, in this respect, this strange (but typical) bit of cross- and match-cutting in Scream and Scream Again:

I don’t have the time to do justice to this feature of the film, though maybe Marsh or Evan will follow through on it come Thursday. For our purposes today, let it suffice to say that compositionally or formally, the film takes the composite-ness of a Hammer Frankenstein film stitched together with a Dr. Mabuse film very, very seriously and in ways that reach down much deeper than its surface loopiness might otherwise suggest. But I digress.

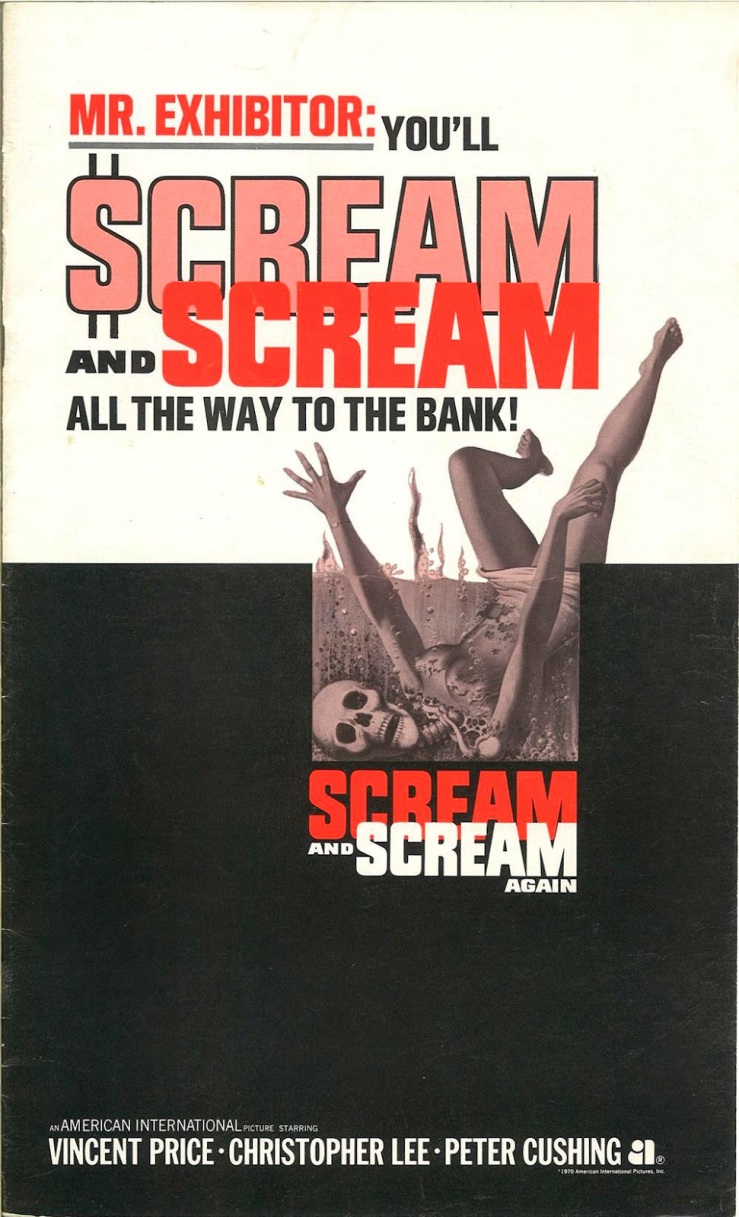

Before I build a bit more on this in terms of Mabuse and bureaucracies, I ought to briefly point out here a final thing, which is that it should be of interest to all of us that Mabuse gets confused with just another mad scientist in the first place. That is to say, it is not a mistake that Germany’s biggest horror icon gets mis-identified as one of Great Britain’s biggest horror icons in a film that actively seeks to negotiate the film traditions and cultural properties of these two nation-states. I would further note that the presence of Vincent Price here muddies things even more because what we effectively have here is a figure who’s part-Frankenstein, part-Mabuse, and part-Edgar-Allan-Poe-villain (if we take Price’s wildly successful run as the villains in AIP’s Edgar Allan Poe adaptations of the early 1960s as the horror roles with which Price likely would have been most popularly associated at this time). In short, Price’s Dr. Browning certainly is a composite himself, not just in terms of the film’s plot but also in terms of the film’s use of horror iconography, which mashes together a giddy concoction of times, places, and figures that are not at all reducible to each other. There’s obviously a lot more to be said on this point, but I just don’t have the time to say it.

The next thing that we would want to note concerning Dr. Mabuse and Scream and Scream Again is that the sort of utopian fantasy that Dr. Mabuse names is that there is such a thing as a smoothly functioning bureaucracy. To put it more pithily, to believe in the threat that Dr. Mabuse poses is to believe that somewhere in the world there’s a bureaucracy that’s working—maybe not flawlessly, but more efficiently than any other bureaucratic structure ever yet realized in the history of mankind. It’s an entirely illegal and shadow bureaucracy meant to overthrow existing social structures and their attendant bureaucratic arrangements, to be sure, but that shadowy and shady bureaucracy of Mabuse’s is a bureaucracy all the same, which is to say that Dr. Mabuse (or rather the person occupying the Mabuse subject-position) spends a damn awful lot of time coordinating the efforts of his criminal underlings and lackeys, who for the most part follow through quite well in carrying out the Mabuse figure’s demands. Consider, in this respect, all the work that goes into carrying out a campaign of terrorism in The Testament of Dr. Mabuse:

Now compare this to another Mabuse-figure from Scream and Scream Again, Fremont, who seems to be a higher-up in the British government:

Two things are worth nothing here. For starters, I would argue that these two scenes (when coupled with the ending of the film) call into question the West German distributors decision to make Vincent Price’s Dr. Browning their Dr. Mabuse because a good deal of the pleasure in watching this film is the guessing game one has to play in order to figure out who is the “real” Mabuse, and a rather significant part of the wit of the film derives from its smart extrapolation from the Fritz Lang films, meaning that Scream and Scream Again takes seriously the possibility that there likely isn’t a Mabuse anymore but increasingly a planet (or at the very least a whole slew of governments) overrun with all sorts of men who would be Dr. Mabuse. Sven Lütticken’s “Planet of the Remakes” has already been remade into a planet of the Mabuses, as it were. That’s my first point.

My second point would be to note that Scream and Scream Again seems committed to removing the differences between the West and the East that Fremont discusses here in a shared bureaucratic solvent. That is to say, both of our Mabuses here, Fremont and Konrad, are quite adept at working their way up the organizational ladder given their seemingly very different social environments, with the result that all this Cold War business involving spy planes and captured pilots gets belied by the fact that at the end of the day what really unites East and West into a unified world system is the fact that there is a super-race of Mabuses likely at the head of both. Hence Fremont’s succinct reply to Dr. Sorel’s question at the end of the movie:

“Is it all over, sir?”

“It’s only just beginning.”

In short, the film seems to be saying there really is no Cold War because there is no systemic difference between East and West; both are recuperable under a totalizing and shared vision of a modernity-to-come marked by impeccably and technocratically managed societies belonging to the new race of suped-up Mabuses.

Another way of coming at this would be to say that being an anarcho-fascist committed to a campaign of mass terror and horror in Nazi Germany and being a group of genetically-modified technocrats committed to taking the reins of world power firmly in their collective hands takes a lot more organization effort to pull off than it does if you’re the Joker in the Gotham City of The Dark Knight (2008), where there’s obviously a pretty big organization behind the Joker’s terrorist acts, but we’re never shown the difficulties of keeping that organization in line. Instead, everything operates seamlessly, as if all the Joker has to do is will it and it is so. Against this vision of the seeming effortlessness of an anarchic overturning of Gotham City, we have in the Mabuse films and in Scream and Scream Again a counter-utopian vision of institutions that finally work. Fremont, it will be remembered, can’t even get the British government to make planes that self-destruct when they’re supposed to, which is precisely the sort of thing that Dr. Browning waxes misty-eyed over the passing of in his final speech to Dr. Sorel as he prospectively describes how the non-evil super-race will run things on ever more smoothly functioning institutional grounds: when the Mabuses of the world set a plane to self-destruct, presumably it will self-destruct and kill the pilot while it’s at it too. Similarly, it ought to be noted that despite the investigative efforts of Inspector Lohmann in The Testament of Dr. Mabuse, the explosion of a chemical plant and the spread of deadly gas from this explosion do in fact take place in that film. In other words, a terrible and very deadly terrorist attack is successfully carried out, and nothing Lohmann or a traitor from within Mabuse’s organization do ends up preventing this from taking place, which begs the question: Well, if Mabuse is such a criminal mastermind, then how does he end up getting his comeuppance?

The short answer is that Mabuse always does himself in, which is to say that there is an arbitrary self-destructive streak in Mabuse, which is a pretty unsettling prospect when you think about it. That is to say, the message of the first three Lang Mabuse films tends to be that you can’t do much to stop Mabuse—all you can do is wait and see how long it takes before he drives himself insane or he “accidentally” drives himself off a bridge. Here’s how Dr. Mabuse: The Gambler ends. While holed up in a secret hide-out where his counterfeit money operation is based, Mabuse gets visited by the ghosts of all the people he’s killed in the film and starts to go mad just as the police descend upon his hide-out:

And here’s how The Testament of Dr. Mabuse ends, with Dr. Baum, our surrogate Dr. Mabuse, going mad and checking himself into his own mental institution, where he sedulously begins tearing up not counterfeit money but rather the last will and testament of Dr. Mabuse himself:

And here’s how The 1,000 Eyes of Dr. Mabuse ends: in a five-minute-long car chase that (much like the one in Scream and Scream Again) stands out both for its arbitrary length and for its arbitrary ending. That is to say, the very belated hailstorm of bullets that greet Mabuse on the bridge seem hardly to justify the over-zealous curlicues and over-corrective steering that leads to his car plummeting into the river. Take a look (it’s a longer clip, but that’s because it’s worth reflecting upon its relationship to the fifteen-minute chase scene involving Keith in Scream and Scream Again):

Now compare Mabuse’s death here to Keith’s in Scream and Scream Again:

If we take seriously this self-destructive streak in the Mabuse films and its continuation into Scream and Scream Again, then we’re now left with the problem posed by the ending, in which we have three Mabuses face off against each other, but not all three Mabuses die. If Mabuse is supposed to kill himself (like Keith faithfully did), then why do we end up with one more Mabuse than we need at the end of the film? The answer to my mind is simple provided we approach the matter of Mabuse’s self-destructive streak in the following terms: it takes a Mabuse to kill a Mabuse, and if you live in a world where there’s more than one Mabuse, then your film need not end with all the Mabuses dispatched to an early grave or an early trip to the insane asylum. That is to say, Scream and Scream Again very cleverly follows out the logic of Lang’s Mabuse trilogy into an ending that that trilogy cannot quite seem to imagine as a possibility, even though it is a conclusion that is entirely thinkable in the terms set up and described in those three films. If Mabuse’s self-destructive tendencies simply mean it takes a Mabuse to kill a Mabuse, then Scream and Scream Again’s Mabuses are easily as self-destructive as any to be found in Dr. Mabuse: The Gambler, The Testament of Dr. Mabuse, or The 1,000 Eyes of Dr. Mabuse.

What also interests me about this ending to Scream and Scream Again is the way in which it strangely overlays British horror iconography onto German horror iconography, particularly in Dr. Browning’s death scene, which I very much believe is an uncanny composite of moves cribbed from Dracula films (both British and American) and Mabuse films. Take a look to refresh your memories:

This is a pretty weird moment and an inscrutable death scene if you don’t have Mabuse and Dracula movies to give you some orienting cues to follow out in interpreting it. If I had the time, I would start by showing you some shots of glowing hypnotic eyes from 1930s American horror films, like Dracula (1931) or The Most Dangerous Game (1932), but I think I can get my point across by sticking with Christopher Lee’s Dracula, who (as you all well know) likes to make people do his bidding seemingly through the hypnotizing power of his gaze. There are countless examples of this, but here’s one of the snazzier ones in which the eyes of Lee’s Dracula mesmerizingly draw a young woman to him on the rooftops of a small Middle European town in Dracula Has Risen from the Grave (1968):

Now compare this spellbinding gaze with that deployed by Dr. Mabuse in Dr. Mabuse: The Gambler. In this scene, Mabuse is disguised as Sandor Weltmann, a world-famous hypnotist, who uses his powers of mesmerism to bring Police Inspector von Wenck under his control:

After having von Wenck do his bidding in front of the gathered crowd to prove his control over him, Mabuse almost successfully has von Wenck kill himself in a horrific automobile crash (the only thing that saves the police inspector are his fellow cops who forcibly pull him from his speeding car just before it goes over a cliff).

Now the gist and pith of all this laborious building up of a mesmeric citational network established by what looks to be a clumsily-put-together throwaway anticlimax is to say that these remaindered bits of Mabuse movies and Dracula flicks aren’t just leftovers, they’re obstinate willful parts that refuse to be incorporated into an integral whole. That it is to say, just because Mabuse and Dracula make heavy use of the power of the gaze to bend people to their will, we’re still left with the seeming irreducibility of those powers (or, more particularly, of the meaning of those powers) to each other. Dracula isn’t Mabuse after all, right?

Well, actually, Dracula is a Mabuse figure, depending on what Dracula film you’re talking about and when that film is set. So long as the Hammer Dracula films takes place in some indistinct nineteenth-century neverneverland, Dracula very much runs a one-man operation of sorts entirely dependent on his face-to-face encounters with his victims, minions, and enemies. Whatever organizational structure might be found here is only nascent—it’s early modern as it were. Interestingly, however, of the 1970s Hammer attempts to bring Dracula into the late twentieth century, the only film to somewhat successfully pull that off was the final one, The Satanic Rites of Dracula (1973), which got rid of all the gothic minion nonsense of Dracula A.D. 1972 and realized that the really scary prospect of a Dracula in the late twentieth century is the possibility that he would integrate far too well into existing society such that he could be both a multi-millionaire property developer (operating under the alias of D.D. Denham) and the head of a multi-billion dollar foundation without anyone being any the wiser. That is to say, what Scream and Scream Again anticipates is that Dracula really is a sort of Mabuse-figure in potential, and all that held him back from becoming one and the only thing that held us, the viewers, back from recognizing as much is the story of capitalist development itself. In other words, with the onset of something like modernity throughout all the zones of Europe (East, Middle, and West), Dracula has to get his act together, put together an alias, stop relying on time-consuming face-to-face encounters, and start putting his plans into motion through massive corporate structures that allow him to get at millions of people and at a distance instead of a handful of people and far-too-up-close.

In short, the argument I’m trying to map out here is that Scream and Scream Again suggests that Dr. Mabuse may have been in drag as Dracula all along. Who’s to say otherwise, especially when you get taken to the police station and the bobbies start asking you to help them to put together a composite sketch of villain? Don’t all men start to look alike? Doesn’t Scream and Scream Again’s composite nature make the composite image of the threat it presents start to look ever and always like Mabuse?

I want to end this lecture by pointing out the problem with this reading and by pointing to what the next move an interpretation of this film would have to make. In a nutshell, the manifest shortcoming with a Mabuse-explains-it-all reading is that it buys a bit too much into a progressive philosophy of history. That is to say, if we stay stuck reading Scream and Scream Again in terms of Dr. Mabuse tropes and moves that ever and always trump pre-existing British horror movie ones, then we’re basically reading this movie far too teleologically, as if Mabuse were at the end of every horror road in Europe. As much I see the film doing something like this, I don’t entirely buy a reading of Scream and Scream Again in which all Frankensteins and Draculas are Mabuses-in-potential that only need to be brought into the twentieth century for that relationship to be unveiled for once and for all. The obvious limitation with this interpretation is that it is still too personal. If Mabuse really is supposed to be some sort of “image of the times” for much of the twentieth century, then it’s an image that eventually starts to get things more wrong than right about those times by insisting far too much on the figure of Mabuse itself, which is hardly consonant with the world we all live in and have all lived in since at least the 1970s, for in this world there is no magic name we can incantatorily invoke to describe (much less solve) all our problems.

Saying Mabuse or, for instance, J. Edgar Hoover is the person listening in on your phone calls or filming you in your hotel room is almost a non sequitur because the category of privacy itself had already started to evaporate by the time of Scream and Scream Again such that the question of the subject-position at the head of the organization carrying out these unseemly surveillance operations was altogether moot. In short, the problem was no longer who was surveilling us but rather that there was surveillance of everyone everywhere all the time in potential. That is to say, the epistemological problems sketched in by Fritz Lang’s first three Dr. Mabuse movies (which can be re-phrased as the question, Who is the real Dr. Mabuse?) become ontological ones by the early 1970s (in other words, the subjugation of masses of people in the West to invasive organizational forms that maybe mean them no good simply became a condition of being or of existence for those masses by the 1970s such that the revelation of who was behind it all became a silly thing to undertake because no one really believes any one person is behind anything anymore really because the problem has become global and it has become deeply structural in nature).

What I am trying to sketch in here is not the Mabuse-like progress narrative described by Scream and Scream Again’s ending but rather a mutation in narrative itself. Instead of creating a new villainous figure to take over the reins of Mabuse, Frankenstein, and Dracula, films of the 1970s (particularly American films— Parallax View [1974], The Conversation [1974], Three Days of the Condor [1975], All the President’s Men [1976], Marathon Man [1976], Invasion of the Body Snatchers [1978], Winter Kills [1979], Blow Out [1981]) start to focus instead on the ontological obstinacy of the conspiracy form itself. Instead of becoming invested in unveiling the puppetmaster pulling the strings behind the scenes, these films become increasingly committed to exploring the texture of social experience and sociability itself in a world where everything (even the most intimate moment) is a public matter and can be made to stand in for something else in way not of your own choosing.

I want to close with that point by suggesting that Scream and Scream Again isn’t quite as Mabuse-crazy as I might have led you to believe because there are moments throughout the film that manage to think outside the Mabuse-box and envision something like these American conspiracy films that were just around the corner in 1969 and 1970. Compare, for instance, this scene from Scream and Scream Again with the opening of Francis Ford Coppola’s The Conversation. First, the meeting of Fremont and Konrad in Trafalgar Square:

The sorts of things I want you all to notice here are the long-range, high angle-shots of Konrad crossing the square to the fountain and the long-range shots of Fremont coming down the stairs because they open up an eerie space in which high-level transactions between Cold War enemies unfold in plain view of an unsuspecting public that nevertheless may be listening in (for instance, the question here that almost gets raised by the film is, Who’s operating that rooftop camera that zooms in on Konrad? Is it the film itself or is it someone/something from within the diegesis of the film?). To be sure, this disquieting framing of the meeting of Fremont with Konrad quickly enough breaks down into the more familiar two-shots that re-instigate something like a private space in the middle of Trafalgar Square, but the looming openness and permeability of the space around them which gets set up in the establishing shots doesn’t entirely go away.

For one thing, Coppola’s The Conversation picks up on it and decides to shoot its credit sequence and much of the sequence that follows using similar high-angle long shots showing us a variety of people (but mostly one man and one woman) walking around Union Square in San Francisco while a group of men with surveillance equipment try to record their conversation from rooftops and open windows around this very public space:

The rest of the movie ramifies outward from one garbled sentence that the couple later exchange (“He’d kill us if he got the chance”), which Gene Hackman’s character interprets and re-interprets and misinterprets in a variety of self-destructive ways. That is to say, this movie (like most American conspiracy movies of the 1970s) does not care all that much with who’s responsible for mass surveillance. We already know who’s doing it here: Gene Hackman’s company. To be sure, there’s the question of who hired them to do it, but The Conversation doesn’t much care about that either. Instead, it’s invested in the problems raised by hermeneutics itself, which is to say, if everything we say and do is a public matter, then there’s still the problem of interpretation, of someone sifting through all we do and say and making heads or tails of it somehow.

Which is a long roundabout way of saying we’re back where we started with Scream and Scream Again, faced with the problem of making heads or tails of a film at least as ambiguous as a barely-heard sentence uttered in an undertone next to a blaring street musician in Union Square in 1974. Mabuse won’t help you find a way into The Conversation, and he won’t help you after a certain point with Scream and Scream Again. What will, however, is the simple fact of the conspiracy itself and its globe-encompassing ramifications, which elusively promise to tell you something about the world you live in, even if that world is a pop cultural composite made up of indistinctly placed totalitarian regimes, of vampire serial killers, of bad pop bands who only know how to write one kind of bland pop song, and of superhuman technocrats secretly embedded in positions of power. What else does this composite name if not the problem of trying to give it a name in the first place, like that of Mabuse, who by the late 1960s is no longer able to tie all the detritus of social and cultural life together into a cohesive and life-threatening whole. You don’t need to go to movies to experience that anymore. All you need to do is go for a walk in a park or stroll around Union Square on your lunch break.

[…] Here’s the lecture I gave on The Quatermass Xperiment (1955) and Quatermass 2 (1957) during the British Horror Film course, for which I also dealt with Tod Slaughter and Scream and Scream Again (1970). […]

LikeLike